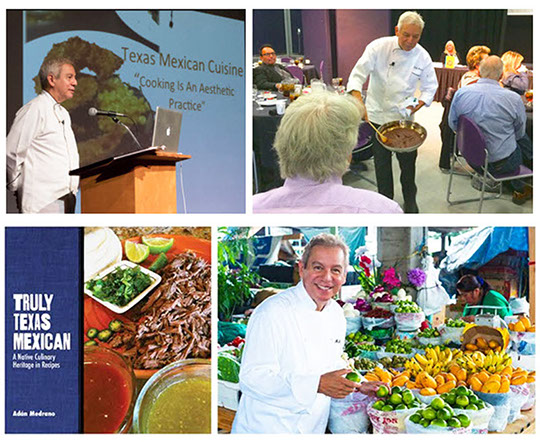

In just three short years at Lone Star Literary Life, we’ve developed a lot of traditions and recurring features. One of our mouth-watering favorites featuring a cookbook author as the front-page Lone Star Listens feature on the Sunday before Thanksgiving. For 2017 our cookbook author and chef is Houston resident Adán Medrano, who has traveled extensively before returning home to Texas seven years ago to turn his time and attention to researching and gathering the stories and recipes behind the food heritage known as Texas Mexican. After sampling is Carne con Chile at the Lubbock Book Festival a few weeks ago — where he presented a cooking demonstration and luncheon in partnership with cookbook author Angelina LaRue and food prepared by Texas Tech’s Top Tier Catering — we spoke with him this week via email about cooking and writing and he even shared a recipe with us for Thanksgiving.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Where did you grow up, Adán, and how do you think it influenced you? As a chef? As an author?

I grew up on the Westside of San Antonio, Texas, the economically poor side of the city, in a house that my father, Juan, constructed with his own hands and those of our extended family: uncles aunts, cousins. My mom, Dominga, owned land with pecan orchards in Nava, Coahuila, just twenty-five miles south of the Rio Grande, by Eagle Pass, so we’d constantly drive back and forth between our two homes and, eating along the way, that’s how I learned the tastes and aromas of Texas Mexican cuisine. River fish blackened on a skillet, avocados plucked straight from the trees, and eating them with just a sprinkle of salt, smashed onto a steaming fresh corn tortilla. Pecans, mesquite, roasted meats, salsas with chile de arbol (thin, dried aromatic chile) — to this day, those tastes, the nuances and honesty of food, guide my cooking, my recipes and writing.

You took quite a different path to becoming a chef and ultimately, a cookbook author. After getting your master’s from UT in broadcast and film, you worked in film, including forming the first Latino Film Festival in San Antonio. What inspired you to make the transition from visual arts to culinary arts?

To move from a filmmaker to a cook was natural and effortless for me. I love making food and film because both are powerful carriers of our identity. Both are cultural expressions of who we are. Both are fun. To me, a shared movie/media is where we collectively dream, and the dining table is where those dreams are affirmed and nourished.

I founded the San Antonio CineFestival, the first ever Latino film festival in the U.S., because grassroots filmmakers in San Antonio’s Westside and in many other barrios across the entire U.S. were making beautiful films/media, but were unrecognized in the general marketplace. I wanted the general marketplace to enjoy those films. Today the San Antonio CineFestival continues as the national celebratory space of Latinx filmmakers. It’s a revolution, in some ways, because of the happy marriage between film and food through social media, streaming video and personal blogs.

The food in Mexican American homes in Texas has always had the home kitchen as that established, celebratory space where creative cooks produce delicious dishes and share them with family and friends. But, as in film, the food is unrecognized in the general marketplace. I want this food to be shared more widely because it’s so delicious and also because it can promote understanding. Just as film/media are superb when they advance insights and ideas, so also food is at its most delicious when it promotes understanding, when it is intellectually delicious.

That’s what drove me to write a cookbook, the desire to communicate, to share delicious food that is more than just feeding, to describe its rich cultural and social context. I think that food divorced from culture has no legs.

You then spent twenty-three years traveling, working and cooking across much of the globe. Can you tell us what prompted that decision and what was it like?

Using my experience in media, I worked as a philanthropist, a foundation officer funding media projects in Europe, Asia and Latin America. The work inspired me, meeting many visionary, courageous leaders who worked selflessly to build societies of justice. They were happy people, leaders who served. They enjoyed and shared food with me as a way to welcome, and also to help me learn about their culture. We often cooked together.

As I dipped a slice of cucumber into Thai nap prik chile sauce, friendships formed and I saw how food connects us globally, but can only be enjoyed locally. Gobbling my bowl of goulash in Budapest, I committed to buying some local Hungarian cookbooks, to learn about the food. But I didn’t have to, because my host gifted me with some, knowing how much I loved food. Now, in my kitchen, many such memories ground my cooking.

About seven years ago you returned to the U.S. and then graduated from the Culinary Institute of America (CIA). What turns did your life and work take then?

Jetting all over the world eight months of the year got to me after twenty-three years, so I decided to change careers and spend my time at home, in Texas. I turned my focus on food, my second love. I had worked in restaurants and had deep knowledge of home cooking, but I wanted professional training and the chance to engage with other culinarians. The Culinary Institute of America was a wonderful experience that fulfilled both interests.

I’ve been able to blend the CIA training with the skills and knowledge I learned in many Mexican American family kitchens. To this day, my culinary compass is my mother’s kitchen.

You’ve done quite a bit of research about indigenous Texas Mexican food compared to Tex-Mex. Can you tell us the differences between these two kinds of foods?

It took me three years to research the archaeological record and the historical texts that I talk about in my history/cookbook, Truly Texas Mexican: A Native Culinary Heritage in Recipes. In the book I explain that Texas Mexican food is a unique cuisine with a history that archaeologists trace back 10,000 years, to the culinary traditions of the first Native Americans of Texas: Karankawa, Tonkawa, Coahuilteca, Caddo, and hundreds of other culturally rich communities. It isn’t south-of-the-border cuisine, because its historical roots are to be found north of the Rio Grande, in places [that we now know as] Corpus Christi, San Antonio, Waco, McAllen, and El Paso, where it developed and flourished centuries before the river became the US-Mexico border.

The traditional Mexican food of Texas is not “tex-mex,” the hyphenated term that began to be used in the 1970s, referring to a type of food found only in certain restaurants, characterized by a reliance on shimmering high fat, lard, sour cream, and mounds of melted yellow cheese. Some of my friends and I have gleeful memories of celebrations where we enjoyed the popular tex-mex restaurant food, but that’s not my family’s food. We don’t eat like that.

The food that I grew up eating is called “comida casera,” the home style cooking created and enjoyed by Mexican American families of Texas. Just as Oaxaca Mexican food represents an identifiable indigenous region of Mexican cuisine, as do also Jalisco Mexican food, Puebla Mexican food and others, so too Texas Mexican food is a unique indigenous regional type of Mexican food.

It’s Thanksgiving week in the U.S. Are there certain foods that are a part of your family’s traditions? Will you tell us about them?

Well, don’t be astonished, but my dad always had a fresh chile Serrano on hand, and took bites from it as he enjoyed the “guajolote,” turkey. Actually, I now do that sometimes. Guajolote is indigenous to Mexico, so of course it pairs with chile, and it’s a Thanksgiving tradition in our family. We also enjoyed green peas, giblet gravy, mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, and chile Serrano salsa. My mother, amá, made a special cornbread dressing with pecans, bell pepper and raisins. So delicious. Okay, next question — my mouth is watering.

How long did it take for you to write Truly Texas Mexican, and what was that process like?

I worked on my history/cookbook three years, including the last four months that I spent in my test kitchen cooking, tasting, re-cooking, and correcting each recipe. I ate a lot.

The process involved three sources of knowledge. First, the archaeological record to find out the ingredients and cooking techniques of the first peoples of Texas, the ancestors of today’s Texas Mexican American community. Second, historical documents beginning in the 1500s that reveal the hunting, gathering, and cooking habits of the many cultural groups in central and south Texas. And most importantly, I spent many days with my brothers and sisters, recalling stories and recipes. Together, we tasted our family’s traditional food, to make sure that I recorded our experience faithfully, and that the taste, the enjoyment, replicated the dishes we enjoyed in our extended families.

It was a work of love to share one hundred delicious dishes and the stories about how they came to be. I think it is a step that, together with other cookbook authors, moves us to prepare a table where all are welcome.

Is there one special recipe you’d like to share with our readers — maybe that they could use to add a different dish for Thanksgiving?

I think you’ll really love my amá’s cornbread dressing with pecans, bell pepper and raisins. The cornbread has a low amount of fat and isn’t sweet. Nor does it use sage, an herb that is commonly used in most other cornbread dressings. I always serve it for Thanksgiving.

The recipes for making the cornbread and the dressing are above, at left.

On your blog you say “media and food are my two passions” — we’d love to hear more about that.

Both film and food were formative in my childhood. Watching movies on TV, I Love Lucy, and always being able to linger in the kitchen while my mother cooked, these experiences taught me about who I am, who I can become. It’s about pleasure and the love of sharing. I love eating as much as I enjoy watching a good show or movie.

Cooking is pleasurable, I love to make stuff, just as I loved making the weekly TV series on Univision TV Network that I produced, and the documentary about the AIDS epidemic that I wrote and directed for PBS. Passion is what drives a good cook, as it does also a good filmmaker. Cooking and making media both require the same organizational skills, the ability to collaborate, a respect for history together with the joy of innovating. I like to have lots of fun.

What’s next for Adan Medrano?

My next book! I’ve finished writing my new book, tested all 100 new recipes. It will be released the summer of 2018 by Texas Tech University Press.

I’ve included more baking recipes, traditional cookies and pastries, and more innovative recipes like “Mesquite Candy Balls” and “Serrano Chile Stuffed Quail.” It’s about how Texas Mexican cooking is being renewed today, in exciting ways. I also tell the stories behind the food, how food is really hospitality, being generous to others, being open to change. The title of the book is Don’t Count The Tortillas: The Art of Texas Mexican Cooking.

* * * * *

Leave a Reply