Back in the sixties, our country’s biggest demographic was just coming of age. I, too, was a baby boomer. We were young but we elected a president, stopped a war. Universities were the proving ground—where you could walk in on merit and pay tuition with grades—and we transformed them. At times, it seems that for this first generation with effective available birth control, it was all about love, love, love, but there was so much more: the sexual revolution, yes, but also its consequences, and also Vietnam, civil rights, assassinations and runaways, astronauts and LSD.

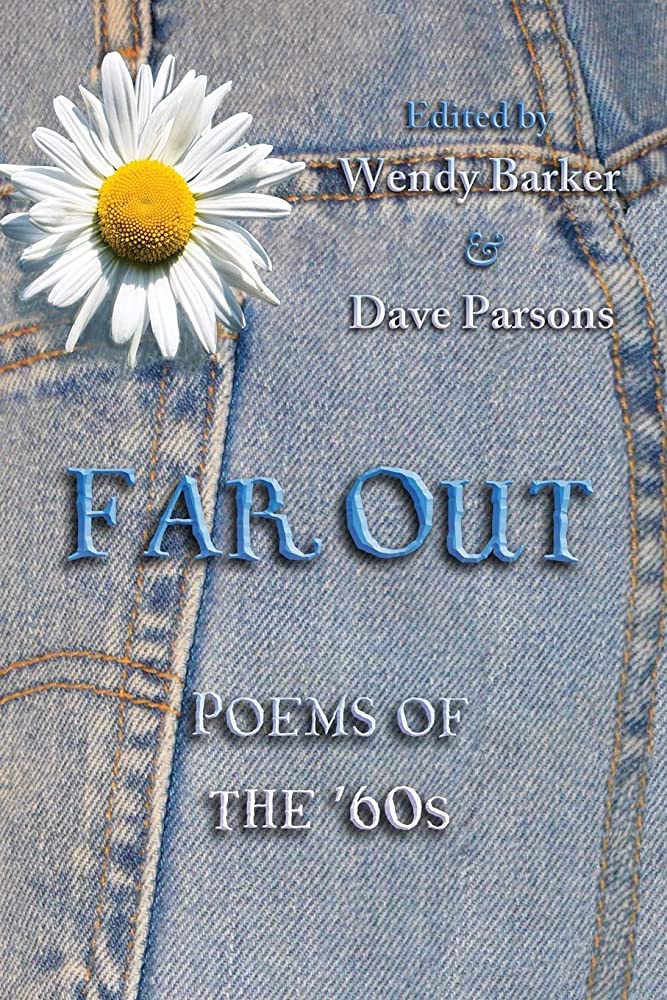

When Wendy Barker and Dave Parsons set about to create the terrific new anthology Far Out: Poems of the ’60s (Wings Press, 2016) they intended to make a history book of a different order built of voices and art and memory, a form perhaps better suited to capture the more fleeting aspects of an era. In Far Out they assemble poems of personal history gleaned from current poets of note from across the United States to give us a sense of the era through the eyes of those who were in the crowd. Far Out functions beautifully in that regard; the book hands us the heart of the time, the God-in-the-details vividness of it all. But for better or worse, Far Out has also landed in 2017—this book should become an important resource for resurged interest in poetry of resistance, or, I should say, about a time of resistance.

Back in the sixties, Barker was teaching at Berkeley, a hotbed of activism, while Parsons was a student at the University of Texas at Austin. Both feel they were in epicenters of the decade.

I started the book wary of misty-eyed nostalgia and too-easy references to top headlines, and I found some of that, but soon, sensory impressions, layers of memories, anecdotes, and stories built and layered inexorably into a colorful multi-dimensional view of that time. Yes, you will find reefers and tear gas, dropouts and civil rights volunteers, but there are also just plain people populating an “America young enough to break out in pimples.” Picture at the beginning of the era, as does poet Chana Bloch, a girl in pointy shoes, pointy bra, and helmet hair in a perfect flip trying too hard to impress a man while waiting to break out of her chrysalis, as another runs braless in sandals with wispy waste-length hair that she has braided with flowers. There’s the quaintness of door-to-door activism, of risking jail time without fear of prison, of campus sniper Charles Whitman as an anomaly, of passionate youth who live in three dimensions with no digital age in sight and feel responsible for change. It’s all in this absorbing collection of work by poets who are all connected to that era. ”If you lived it, Parsons says, “you were marked by it.”

In Far Out, Janis Joplin is a best buddy’s shy girl in Beaumont, Texas, who sometimes plays guitar. Stanley Plumly tells us, “Ralph (Abernathy) said the numbers finally didn’t matter/the idea of change was enough.” Yusef Komunyakaa finds himself back in Vietnam surrounded by klieg lights, phantom jets, and artillery fire as Hanoi Hannah taunts, “You’re lousy shots, GIs, ” and then “her laughter floats up/as though the airways are/buried beneath our feet.” Then we’re back in the States singing our hearts out as Barbara Hamby assures us rock ’n’ roll was “heaven sent as our own voices/were we human enough to heed the call.”

Barker and Parsons worked for six years on Far Out, soliciting, collecting, then sifting the poetry looking for a particular uniqueness that somehow spoke for many. Their goal was the overall picture—they made no attempt to differentiate between poems written during the sixties and those that look back on those times. I questioned this, and the academic in me still wishes to have that authentic stamp as a relic of the decade clarified where it applies, but I have to say for sheer readability of the volume as a whole, to get a sense of the era, their approach works.

Near the end of this over-three-hundred-page immersion, Kevin Clark tells us, signifying the end of the decade, “I sometimes think of Nixon/how he failed us all.” But it was the last line of the book, from Robert Bly in his poem “1970” that haunted me: “and the war was over, almost.” Almost. Lingering on that last word, it seemed the era itself had no end.

Leave a Reply